Guide to Testing an AI’s Memory

Easy to Build, Hard to Evaluate

It’s been a while; I have been busy with Ting doing CTO things. A couple of months ago, we introduced memory into Ting. These are small sentences that encapsulate things that Ting deems relevant to remember about your scheduling habits, so that it can do a better job. I wrote a nifty guide on how to get the most out of it for our users and everything (and if you are a user you can see them here). But today I want to write about what goes on behind the scenes of a feature like this - one that needs continuous evaluation and improvement, as it will never truly be done.

Deceptively Simple

Introducing memories can sound simple; there are already a lot of tools out there promising to plug-and-play into your existing Agent. As the AI person I am, I like having full control and have unfortunately been burned too much by using ready-to-use solutions and have greatly enjoyed my work when I was the one doing API calls to LLMs in Ruby back in 2023.

But maybe it still sounds simple enough to introduce a prompt that says, “Is there anything you need to remember about the user’s scheduling habits? If yes, what? Otherwise, reply no”. That is a great first version, but will it work well enough?

What's Worth Remembering?

Figuring out what it means for memories to “work well” is the first step in any implementation. Even though it might seem that memories are always the same regardless of the product, that is not true. The definition of what is worthy as a memory in general-purpose LLMs needs to be a bit more overarching than something like Ting. For Ting, if it doesn’t affect your calendar or your meetings, it is noise.

What we are trying to do at Ting is to make your scheduling experience better. So what we want to remember are facts/preferences that make your scheduling experience better. For example, are you a meetings-in-the-morning kind of person? At the same time, since Ting is multi-player and interacts with guests, for privacy, we don’t want to remember information about your guest or your private meetings and leak them across conversations. Two simple requirements that already justify a custom solution.

Write it Down

So before any prompts, any code, any testing or evaluation, you need to write down what you actually want out of memories - no technical skills required - and be as specific as possible. This is also the time to avoid making any assumptions about what the AI can and can’t do, and just write down the examples of what you wish the AI to do. And let’s start from the end, assuming infinite memories already exist. Ask yourself what the Agent could know about the user that would change the response. Here are the kinds of examples we wrote down for Ting:

Incoming email: “Let’s meet next week” → Retrieve Memory: “User doesn’t like morning meetings.” → Desired Effect: Suggest meetings in the afternoon.

Incoming Email: “Let’s meet after the 5th.” (sent in 2025) → Retrieve Memory: “User is on holiday from December 1st to December 7th 2025.” → Desired Effect: Suggest slots only after the 7th. Do not include slots between 5th and 7th.

Incoming Email: “Are you available for an interview tomorrow at 9 am?” → Retrieve Memory: “User is on holiday from December 1st to December 7th 2025.” → Desired Effect: An interview is too important, so we might still want to say yes.

There are already two dimensions here to evaluate: the first is whether the right memory gets retrieved; the second if it is used correctly. Since memories need to be created/updated/deleted, the next step is to think through what kind of language would trigger changes to our memories. For example,

User email: “Can we move it to the afternoon? I hate morning meetings.” → Memory: “User doesn’t like morning meetings.”

User Email: “Hey Ting, I’m going to be on holiday first week of December.” (sent in 2025) → Memory: “User is on holiday from December 1st to December 7th 2025.”

User Email: “Actually, I’ve started to enjoy morning meetings lately.” → Remove memory saved in 1

User Email: “Actually, I prefer morning meetings now.” → Update memory saved in 1

User Email: “Can we move our meeting to the afternoon?” → Save nothing, not a scheduling pattern

Your initial set of examples should be as exhaustive as you think will be needed, but as sparse as possible to allow for iteration speed in development and debugging. And with everything evaluation-related related I recommend using the least amount of AI possible, and really use your human brain for examples.

Another good thing about writing this down is to ground the discussion and make the different assumptions team members might have on what memories should be saved clear before time is wasted in prompting and development. For example, someone might point out that 5 could be a pattern we would just have to look at multiple emails, which would be a good point, so we could maybe rewrite to create memories from batches of emails instead of individually and rewrite the list according to this new paradigm.

Three Datasets for One Feature

An added complication of memories, as you can see, is that our examples are not simply one-to-one mappings as most evaluation guides and frameworks assume AI features are (and a lot of our other Ting features can be evaluated like that, so still valuable). In practice, this means we need to have 3 evaluation datasets:

1. Extract Memory

Input: Incoming user emails and messages (one at a time).

Output: Create, Update, or Delete operation in the memory dataset

Metric: Did it pick the right CRUD operation? Does an LLM-as-judge consider the new memory content to match the expected ground truth?

2. Retrieve Memory

Input: Incoming user emails and messages (one at a time).

Output: Retrieve a memory from the memory dataset

Metric: Did the system pull the relevant memory from the database given the input?

3. Apply Memory

Input: Incoming user emails and messages (one at a time) + memories output from step 2 (if any)

Output: Response to user

Metric: Does an LLM-as-Judge consider the output email to match the expected ground truth?

Once we split up the problem like this, we can just follow the guides and best practices on AI evaluation. You can diagnose exactly where the system is failing. If Ting suggests a morning meeting when I hate them, I can look at my datasets and see:

Was a memory about me hating morning meetings created at all?

Did we retrieve this memory at the right time, for example, when I asked for “next week” slots?

Or if we did extract it, did the scheduler fail to apply it?

Real JSON From Ting

In Ting, we record our datasets in JSON files and then run custom scripts for evaluation. In our memory creation dataset, we check for the change in the number of new memories (a proxy for create/update/delete actions) and pass patterns we want and don’t want to a simple LLM-as-Judge. Here is an example from there:

{

"testCaseId": "update-memory-001",

"description": "User expresses that they have learned to enjoy morning meetings, should update existing memory.",

"input": {

"message": {

"textContent": "Actually, I've started to enjoy morning meetings lately.",

"receivedAt": "2023-10-27T15:00:00Z"

},

"existingMemories": [

{"id": "550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000", "content": "User doesn't like morning meetings."}

]

},

"groundTruth": {

"containsPatterns": ["User enjoys morning meetings now."],

"avoidPatterns": ["User doesn't like morning meetings."],

"numberOfNewMemories": 0

}

}Running our script gives us a neat little summary like which we use to decide whether or not our prompt is ready for production.

📊 Memory Evaluation Summary:

Total Test Cases: 10

✅ Passed: 10

❌ Failed: 0

📊 Pass Rate: 100.0%

⏱️ Total Elapsed Time: 23.62sIt’s a small number of examples for now, because we believe the best examples come from Ting's interactions with our users, and we don’t want to just optimise for our imagination. We already had a dataset to evaluate email interactions, so we just added some memory as a field for examples there as well.

As for retrieval, we are currently passing all memories to our LLM. This was a deliberate choice because we think we can capture all we need about scheduling preferences in a list of 15. So we want to optimise our model for good self-contained memories instead of letting them grow. At the same time, this is a good start-up trade-off example; instead of spending time on RAG implementation, we are spending time on saving good memories and using them well, reducing us to 2/3 of the problem.

Don’t Forget to Design for Failure

Even with all the AI evaluation in the world and the best metrics, we might still save a memory that we shouldn’t, so we need to give the user options to delete it. So, besides thinking through the evaluation list, we should also think through minimisation efforts.

In our case, at Ting, we added a dashboard where we give freedom to the user to create their own memories and delete existing ones. In the future, we plan to also routinely remind users of what memories we have about them so they can act on them without forgetting.

Memory Evaluation Checklist

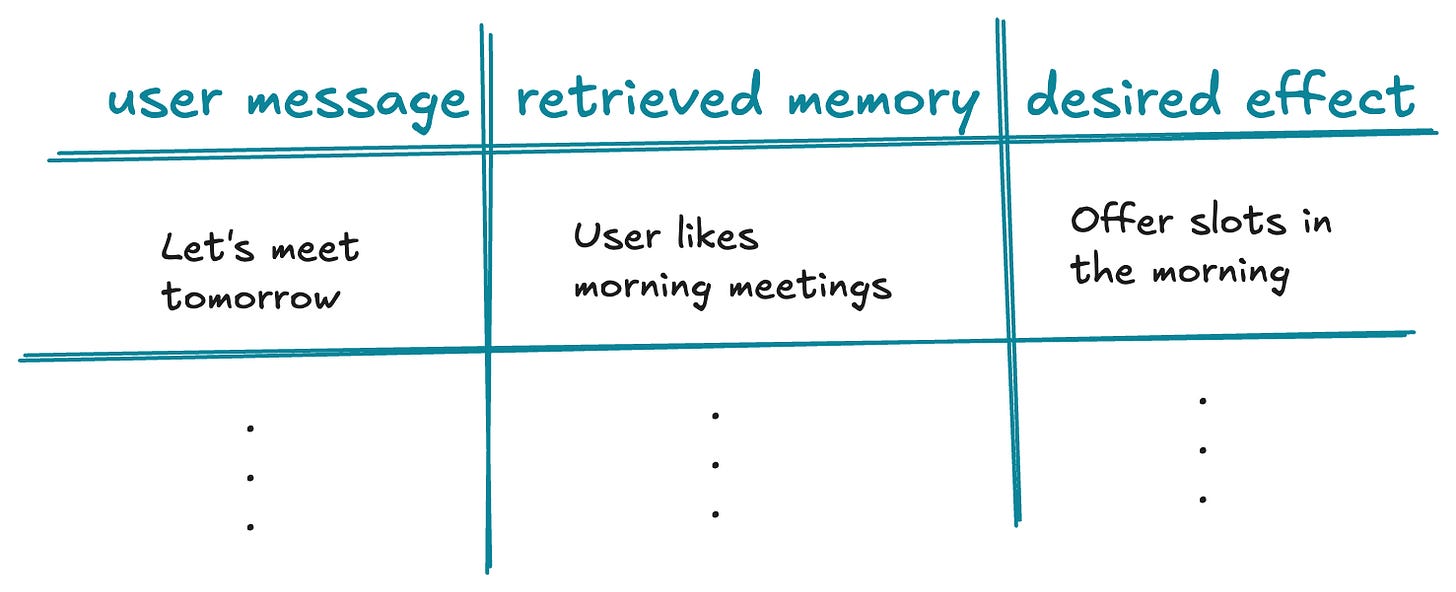

Draft your "Retrieval & Effect" Table: Create a table with columns user message, retrieved memory and desired effect.

Add at least one of the following:

Conflict Tests: The retrieved memory contradicts the user message. For example, “Let’s meet in the morning” + “User prefers afternoon meetings”

Negative Tests: The retrieved memory is irrelevant to the user message. For example, “Should I prepare anything for our upcoming meeting?” + “User prefers afternoon meetings”

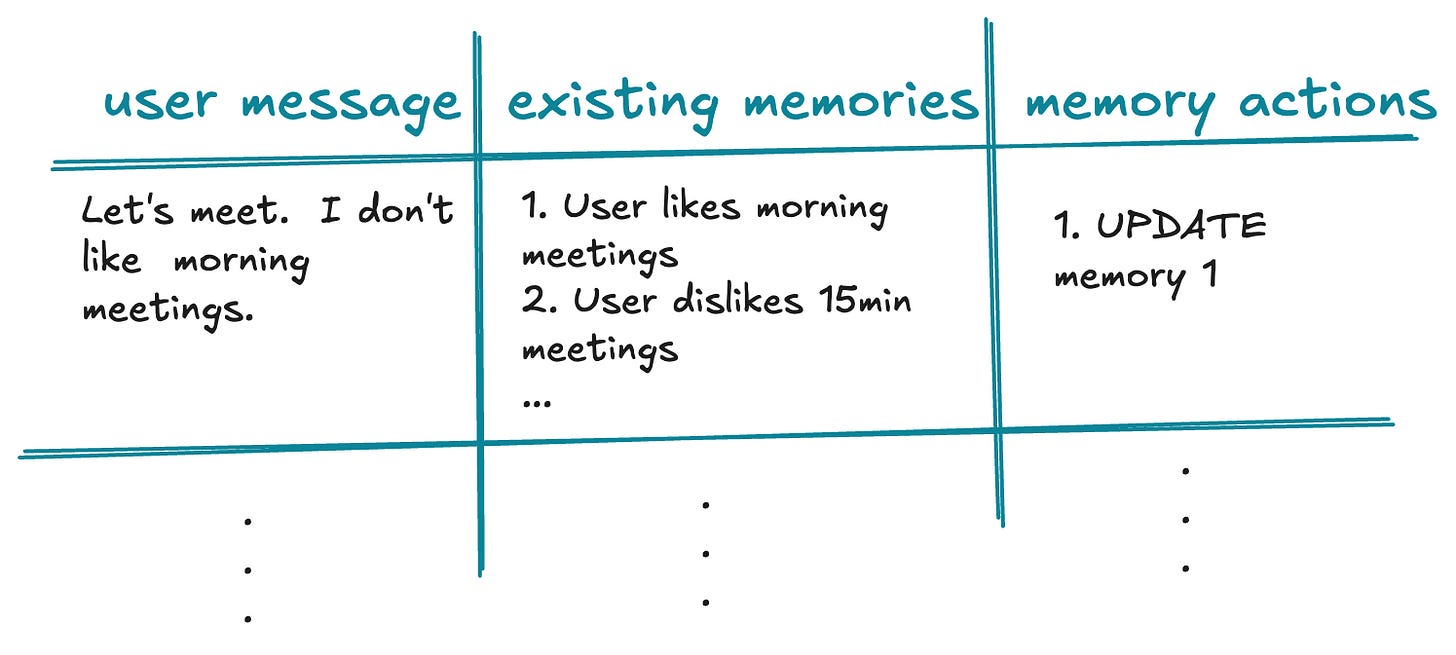

Draft your "Extraction" Table: For each example, write down another table with columns user message, existing memories and memory actions (create, update, delete). Each row is an example you can use later for evaluation.

Add at least one of the following:

Negative Tests: Messages that should result in zero new memories (to test for over-eagerness). For example, “Is 5pm good for you?”.

Multiplicity Tests: One email triggers multiple CRUD operations. For example, “I like 30-minute-long morning meetings”

Align with Stakeholders: Discuss these tables with your team to ensure everyone agrees on the "Ground Truth" before you write a single line of code.

Build the 3 Evaluation Datasets:

Extract: Use the data from your second table.

Retrieve: Map your existing memories to the retrieved memory when the user message matches.

Apply: Use the data from your first table.

Iterate: Now you can start prompting! Refine both code and datasets as requirements change. I talked in more detail about the philosophy of this iterative loop in my talk:

Bonus: Thanks for reading this far! Not every Ting memory is an AI memory. When we want to remember, a user can only take meetings after 9 am, we simply update a field in the database with a tool 🤫 Knowing when not to use memories is just as important as knowing how to evaluate them.